Filmmaker Ton Otto with his adoptive sisters Alup and Asap, Baluan Island 2016. Photo: Christian Suhr

Ahead of the upcoming release of the final film in the Baluan Trilogy, On Behalf of the Living, we invited Ton Otto to talk about his decades-long experience with film as a research tool and how filmmaking became a central part of his relationship with the Baluan Islanders, one of mutuality and respect.

Alice Reiner: Your three films were released over the course of 14 years. In that time, you went from being a relative newcomer at your field site to a very well integrated member of the communities on Baluan, even becoming the son of your adoptive father. How did your approach to filmmaking change or evolve in that time?

Ton Otto: Interesting question! To start with I should mention that I already experimented with video recording during my doctoral fieldwork, before making my first ‘serious’ film. I had no prior experience with filming but wanted to video-document some important events on Baluan to complement my field notes, audio-recorded interviews and still photographs. I also wished to have some audiovisual products that I could return to the local people in addition to my written work. Fortunately I was able to borrow a Mini-VHS camera while in the field. On the basis of my footage and with the help of Patsy Asch at the Australian National University, where I was then based, I produced two short films and presented them in multiple copies to local collaborators. The effect of these small gifts can hardly be overestimated. To the great majority of Baluan people, the films were more important than my PhD thesis and other (written) publications. They were used extensively by the groups involved, both for information and entertainment; and they also helped establish a trust in my capacity to enter reciprocal relations and contribute with useful results from my ethnographic research.

When I started to make films with the ambition to reach a larger audience, I was already well integrated in Baluan society and had been adopted by a Baluan family. This greatly facilitated the openness that people displayed towards the cameras of my co-directors Christian Suhr and Steffen Dalsgaard, who both were MA students in anthropology at the time. Our first film Ngat is Dead shows this intimacy and documents how my participation in family rituals provided an insight into the way traditions can be negotiated and changed. In the article ‘Ethnographic Film as Exchange’ (The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 14:2 (2013), 195-205) I describe how my filmmaking evolved as part of my ongoing relations with the Baluan community. In short, I argue that films should be seen as an element in the exchange relation between a community and their ethnographers and I show how films contribute to the creation of a kind of discursive and reflective space both for local audiences and for the filmmaker-anthropologists.

AR: What were some of the original aims you had for your audiovisual work, and how did your years of fieldwork experience shape and influence the direction it took and the kinds of questions you asked? Have the topics and issues you were interested in changed?

TO: An important original aim was to complement my written work on tradition and change with audiovisual material that can provide dense sensory information that is difficult to convey in writing. Moreover, at that time I was tasked with teaching an introductory course in ethnographic methodology, and I wanted to produce a film that would help students to understand the challenges and potential of ethnographic fieldwork. In particular, I intended to show how researcher participation, for example in local rituals, provides a vantage point on aspects of social action and can highlight how cultural traditions are often consciously brought into play. By being part of the action, the fieldworker also becomes part of the considerations and strategies of people in often conflictual situations with different interests at stake.

Moreover, making Ngat is Dead, which includes a feedback scene that we filmed and integrated in the final movie, taught me how a film project can increase awareness of the cultural implications of filmed events – equally so among participants and filmmakers. It was during that process that I realised that filmmaking with participant feedback and impact can be an important method for the co-creation of knowledge. This sensitized me concerning the relevance of films for local discussions and cultural processes, something we later formulated as its potential for cultural critique (see ‘Camera as Cultural Critique’, special issue of Visual Anthropology 31: 4-5 (2018), pp. 307-425).

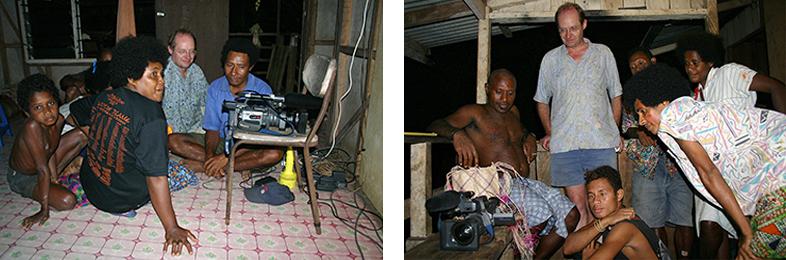

Ngat is Dead. Feedback scenes in 2003 and 2006. Photos: Christian Suhr

In the second film I made with Christian Suhr (Unity through Culture) this internal discussion focuses on the opposition and inherent conflict between inherited traditions and their transformation into cultural performances for the benefit of festivals and international tourism. Needless to say, this focus was also very relevant for my research interest in understanding cultural change. In the third and last film of the Baluan Trilogy, On Behalf of the Living, now including Gary Kildea as editor and co-director, our focus shifted again. By squarely addressing a universal question – is there life after death? – we opted for a cultural critique that was relevant for us as filmmakers but proved equally relevant for our local interlocutors. In other words, the film opened up a dialogue within and between cultural spheres. Because of its topic this film has become very personal and demanded from us as filmmakers that we put our own beliefs and convictions up for discussion to establish a real and honest dialogue with our collaborators.

AR: Over the course of your filmmaking career have you seen changes or shifts in terms of community involvement, community interest and concerns? And in terms of comfort levels of people being filmed (or otherwise involved in the filming process), did that change?

TO: Let me start with the issue of community concern and comfort levels. As I mentioned earlier, I had been making video recordings before starting with more ambitious filmmaking. This clearly made people more comfortable with my filming but also increased their sensitivity concerning the risks of exposure of private ideas and conflicts through public screening. Because on Baluan much knowledge is considered private property, and conflicts can easily escalate, I was very careful from the start to protect people’s private spheres. I learned to take cues from people’s ways of talking, to know whether the things they said were meant only for my ears or for a larger audience. It is often a delicate balance to keep, especially with private conversations, and I always made sure to double check with the persons involved.

On the other hand, oratory performance and challenges to competitors are very much part of Baluan culture. In a way, our films can be seen as an extension of this discursive style transferred to another medium. The success of Ngat is Dead on the island, where our DVDs were screened many times, can be partly explained by the play of challenge and riposte that characterizes some of the filmed exchanges. And wider interest in the film, evidenced by its multiple screenings on national television in PNG, contributed to a communal feeling of pride and ownership. Possibly inspired by this publicity, the main organizer of the Balopa Cultural Festival approached me with the request to make another film, which became Unity through Culture, our second film.

Christian Suhr filming the reconciliation ceremony during the Balopa Cultural Festival, 2006. Photo: Ton Otto

The late Soanin Kilangit, the organizer, had been living in Port Moresby for many years and was clearly aware of the communicative power of film. This is also indicated in the film itself, for example when he says: ‘You are on television’! Making this film, we had to tread carefully because of different participants’ interests and our intention to give a truthful representation of the festival, including the criticism it had engendered. Soanin Kilangit was a good friend of mine and was obviously interested in a positive presentation of the event for local and external audiences. I felt I needed to keep my independence and was able to discuss this with him, arguing that the film would be better, and its impact greater, if all opinions would be represented. Fortunately, he agreed, and we remained good friends. And the film has fed into local discussions about cultural change, as I mentioned already.

AR: In one of the last scenes of Ngat is Dead we see family and community members watching the film, which made me think of Chronicle of a Summer by Jean Rouch. How has community engagement changed, for example: did you receive input or feedback that you took into account/changed as a result, e.g. to respect a local custom or belief?

TO: Concerning your question whether we have taken local concerns and comments into account: This has been the case with all three films, but the process of consultation has been most intensive with the last film, On Behalf of the Living. As also transpires in the film itself, I’ve had many discussions with my closest family members on the island on the content of the film and its message. In addition, I organized several screenings of rough cuts, making sure that all protagonists had seen and been able to comment on the film. Finally, I have individually asked these persons and received their approval of the way they were portrayed including the words chosen to be included in the film.

AR: Entering a long-term relationship with communities also requires fieldworkers to be accountable. How do you think about accountability towards the community in terms of your filmmaking?

TO: I believe that accountability is a very important issue for any ethnographic film project, whether it involves long-term relationships or not. But you are right to suggest that long-term involvement makes this even more pregnant since responsibility and reciprocity have to be sustained over a long period of time. In my case, entering family relations on the island through adoption has resulted in a continuing social obligation towards my Baluan family, both when I am on the island or at home. I need to add that I have never felt too heavily burdened by their requests and that I have only given within my means and possibilities, which was accepted and understood by them. A challenge has been to spread my attention and occasional presents more widely in order to avoid envy being directed towards my adoptive relatives. Especially in the beginning, there were some rumors that I would be making large amounts of money with filmmaking. These ideas have greatly diminished over time, partly because I was able to invite five islanders to contribute to an exhibition at Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus. They were regular guests at my house, and I and many others took them around the region. As far as income generated through the sale of the films is concerned, my co-directors and I have agreed to use this money for supporting individuals and community projects on the island.

Equally important for my sense of accountability is our effort to make films that have local relevance for the participants through our documentation of tradition and cultural change and through the films’ contribution to internal discussion about social-cultural issues. By ongoing consultation, feedback sessions and distribution of DVDs, our filmmaking has evolved into a community interest and the recognition by local participants and anthropologists alike that ethnographic knowledge production is a project of mutuality. Recently, I have been able to extend this kind of cooperation with a younger generation of people of Baluan descent, living mainly in Port Moresby, who acknowledge the value of my combined ethnographic work for their heritage and who collaborate with me in studying the ways Baluan culture is changing through city-dweller and villager relations and the impact of global economy and technology on their society.

Unity Through Culture. Public screening of finished film on Baluan, 2011. Photo Ton Otto

AR: Has the trust you have built up over many years influenced the way you make your films and the outcome of your films? And if so, could you describe a few ways in which trust has played a role?

TO: This is certainly the case. I see this trust, which necessarily needs to be mutual, as essential for filming the kind of participatory ethnography that I have endeavored to promote. As I mentioned earlier, my and my team’s continuing efforts to bring the results of filming back to the villagers on the island – and their relatives in town – has greatly contributed to establishing this trust. As a consequence, trust has been growing over time and this has encouraged people to be increasingly more open towards the camera. For example, it would not have been possible, nor would I have thought about trying, to make the film On Behalf of the Living at the time we shot Ngat is Dead, although both films deal with death. In the latest film we dig much deeper into people’s personal beliefs, assumptions, and uncertainties concerning death and afterlife than in the first. And at the same time, we also expose our own uncertainties, prejudices and beliefs. This process has allowed us to come somewhat closer to what has often been called “the native point of view”, and show how this is always context-dependent, individually variable, sometimes contradictory, frequently tentative, and characterized by keeping different options for framing open, often at the same time. Just as it is the case with our own beliefs!

On Behalf of the Living. Reconciliation between two adoptive sisters, Asap and Ninou, 2016, still from film. Camera: Christian Suhr

Adoptive brother Pwanou explains the biblical verse from which the name of the film derives, 2016, still from film. Camera: Christian Suhr

AR: When conducting research, protecting the wellbeing of our interlocutors is at the forefront of ethical considerations, and in On Behalf of the Living, you and Christian Suhr call someone not by his name but ‘the wise man’ to protect his identity. What measures did you take to ensure that everyone involved was comfortable with their participation?

TO: First of all, I used my knowledge of the participants and the local situation to critically assess the footage for possible ethical problems and risks to people’s well-being and reputation. Of course, this knowledge already played a key role during the recording, as for example shown by the discussion about ‘the wise man’ included in the film. But still quite a few scenes were recorded that could damage certain participants or add fuel to their existing conflicts. This has led to our giving up some sequences that would have been really nice for our narrative, while others had to be anonymized in a way that made them somewhat less effective. At a further stage, I showed rough cuts of the film to different audiences on the island, and this also led to some changes. Finally, I approached all main participants to get their approval for their appearance in the film, and, following new GDPR rules in Denmark, I asked them to confirm this in writing.

AR: And finally, what are some key takeaways for you from making three films, perhaps something you learned during the process that stuck with you?

TO: have been many insights along the way, but I will highlight some that can be directly linked to one or more of the films. Filming Ngat is Dead made me very aware of how people on Baluan, and people more generally, relate to their cultural traditions and how they often consciously employ and change them. Making this film also taught me the importance of audiences, both for local rituals and for filmmaking.

The work on Unity through Culture brought home to me how pervasive the impact of economic and cultural globalization is on local societies, but also how enormously creative people are in integrating new ideas, economic realities, and cultural forms and making them meaningful in the local setting. In contrast, On Behalf of the Living made it very clear, I think, how religious beliefs and convictions are often fluid, tentative, inconsistent and context dependent. Simultaneously they are enormously relevant for people to give meaning to their world and for motivating the actions they undertake in it. One review (in JRAI) links our film to the movement of ‘postsecular cinema’, which I find a useful way of thinking about it. A second important takeaway from this film is how different semantic or cultural domains affect each other, often in a hierarchical way. The focus on family relations helps the viewer understand that the importance of these relations often overrides disagreements on religious issues.

A key takeaway from all three films concerns one of the central aims of anthropology as formulated by Bronislaw Malinowski: “to grasp the native point of view”. I have increasingly become convinced that we can only approach the perspective of others through subjective and empathic involvement in their actions and motivations. This implies being honest and open about our own, including our biases and uncertainties. In my ethnographic practice, filmmaking has been an important means to achieving this dialogic approach, and simultaneously documenting it, hopefully to the benefit of others.